Floating Wetlands: Cleaning Up the Charles River

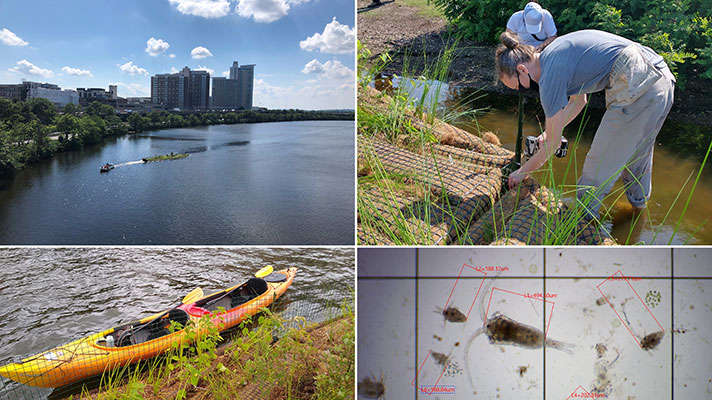

Just downriver from the Longfellow Bridge, there’s a sight quite out of place along the highly urbanized banks of the Charles River. About 700 square feet of wetland floats near the edge of Cambridge. This pleasant piece of nature is not a leftover remnant of the bay’s marshy past, but a man-made structure, the brainchild of the Charles River Conservancy and Northeastern University Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering PhD student Max Rome and his advisor, Professor Ed Beighley.

Many know the Charles River’s historic journey from one of the nation’s most polluted rivers to one of its cleanest urban waterways. This remediation success story represents decades of work by the local, state, and federal government to make the river a safe and recreation-friendly resource for the surrounding community. In the Annual EPA Report Card, the Charles River has gone from a 1995 rating of D to hovering in recent years between a B and an A-. While much has been accomplished, there remains more to be done to ensure the river is safe for swimming.

In 2017, Max Rome came up with an idea for how to improve the water quality of the Charles. At the time, he and Dr. Beighley were working with the Conservancy to assess water quality with an eye toward restored river swimming. His work highlighted the public health obstacle posed by high concentrations of cyanobacteria. Commonly known as algal blooms, an overgrowth of cyanobacteria can pollute water with dangerous toxins and turn it green in color. Cyanobacteria overgrowth is often a sign of pollution by the nutrients they feed on, such as phosphorous from agricultural run-off. Excessive algal growth can also be understood as a consequence of degraded ecology. In a healthy waterbody, zooplankton can effectively control algal growth and serve as an important link in the food-chain. These tiny little animals are themselves preyed on by fish and rely on marshy wetland plants to provide them shelter from their piscine nemeses. The Charles River lacks the vegetation that would shelter the algae-eating zooplankton. Rome’s solution: create a man-made floating wetland.

Through a design grant from the Sasaki Foundation, Rome and the Charles river conservancy worked together to select a site and materials and develop the project. “The zooplankton that are best at eating cyanobacteria are the ones that the fish like to eat the most. In the open river, they tend not to be that abundant,” explained Rome. “The hope is that by creating this novel wetland habitat, there will be a place for them to survive and reproduce more successfully.”

In the spring of 2020, the design was complete and ready for launch. Rome selected a variety of water plants to include in the structure, with an eye towards vegetation that would be pleasing to both humans and zooplankton. “We were looking for a mixture of plants that will be different and interesting,” said Rome. On the banks of the Charles, Assistant Professor Amy Mueller helped Rome and his team bolt together the 22 separate modules of the installation, and they towed it into position just south of the Longfellow Bridge near Kendall Square.

Since then, Rome and his team of four Civil and Environmental Engineering undergraduates have been kayaking six days a week to both the floating wetland and a control plot of the river to collect samples. They then bike the samples over to Rome’s house. “We set up a field lab in my backyard for people to work outdoors while social distancing,” explained Rome. “We started sampling towards the peak of [an algal] bloom. We’ve started to get a sense of the zooplankton population in the Charles.”

From here, Rome, Beighley and their team will collect data and use the findings to understand how wetlands can help improve the Charles River’s water quality. The ultimate goal of the project is not about traditional restoration, says Rome, since the Charles River area was historically a wide tidal estuary surrounded by salt marshes and wetlands. Urban development makes it impossible to return to this original state. Instead “Our task is to be more imaginative of what a healthy river would look like and how that can be achieved, given all the development and restraints on the river.” Ultimately, Rome and Beighley hope that the floating wetland system can be scaled-up into a viable option for municipalities looking to control their algal blooms with a low impact, green solution. Professor Beighley highlights that “Max’s innovating thinking and leadership on this effort have been truly remarkable.”

Rome’s research on the Charles River floating wetland is ongoing. Related degrees for those interested in this line of research include our BS in Environmental Engineering and Landscape Architecture, BS in Environmental Engineering, MS in Environmental Engineering, or our Interdisciplinary and Civil Engineering PhD programs.